Between Heaven & Earth

C. S. Lewis on Asceticism & Holiness

by David W. Fagerberg

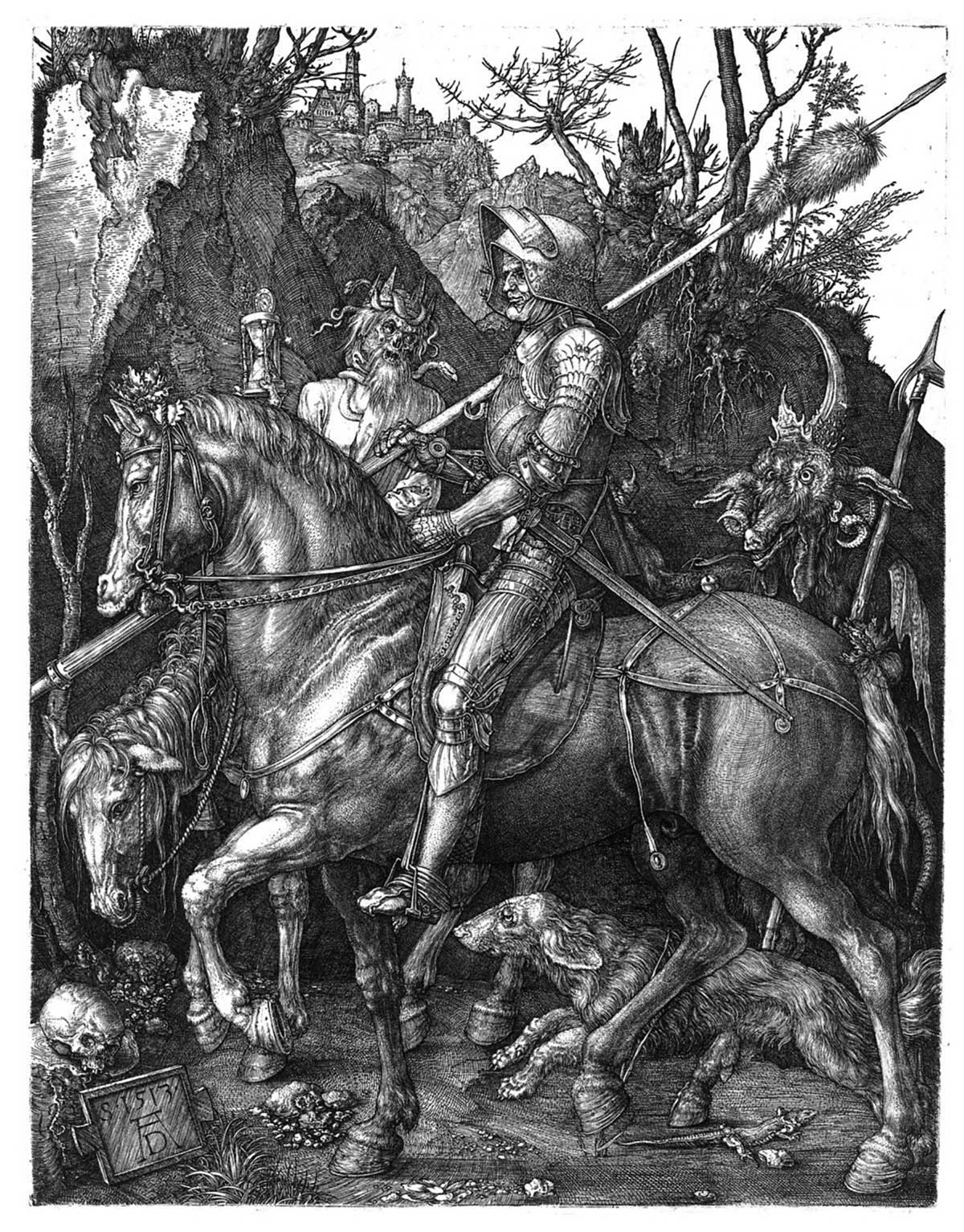

Few words have suffered a worse fate than the word asceticism. It makes us think of someone who is strict, stern, and so excessively and pointlessly austere that he is unable to appreciate the delights of creation. But asceticism did once have a positive meaning in the Christian tradition, and I should like to contribute to the word’s rehabilitation by considering the place of asceticism in what C. S. Lewis called mere Christianity, for it is my thesis that the merest of Christians must be ascetic. The ascetical life may have been perfected in the sands of the monastic desert, but it is born in the waters of the baptismal font, and a Christian without asceticism is like a pancake without flour.

Lewis rarely wrote about asceticism explicitly, but his acute observations of human nature and the patristic and medieval theology he studied were expressed in themes and insights I would categorize as ascetical.1 I might, then, contribute to redeeming the concept of asceticism by uncovering these themes in his fiction and nonfiction, with the aid of quotes from other writers, ancient and modern. I will begin with a definition of asceticism, then consider the role of time in the process, and conclude with Lewis’s images of creation’s transfiguration. (This will assume some familiarity by the reader with Lewis’s work, especially The Chronicles of Narnia and The Great Divorce.)

Hwin the Ascetic

The word asceticism derives from the Greek words askesis, which means “practice” or “exercise” (it was particularly applied to athletes), and askein, which means “to work.” Asceticism is the exercise, the effort, the labor expended to attain a goal. The goal of Christian asceticism is what Eastern Christian theology calls “deification” and Western Christian theology calls “sanctifying grace.” It is union with God by conformity to God.

The Fathers of the Church repeatedly affirmed that God became man so that man might be made divine. Of course, this does not mean that man turns into a deity. Our human nature is not changed into a divine nature, but rather, the life of Christ is shared so abundantly that through his gifts we “share in the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:3–4), are taken up into the Trinitarian relationship of love. Our being conformed to such love is called asceticism. This conformity is effected by both his grace and our response. Asceticism is not our half of the work, but God’s grace conforming us and our participation in that process which itself is caused by grace.

What might this mean? The source of Christian asceticism—the motive and reason and goal of Christian asceticism—is told by Hwin in The Horse and His Boy, when the good and humble mare meets Aslan for the first time. She shakes all over as she trots up to the Lion and says, “Please, you’re so beautiful. You may eat me if you like. I’d sooner be eaten by you than fed by anyone else.” Eating is a metaphor we use when we want to describe a love of a particular sort of intensity. What parent has not tucked a child into bed, with hugs and kisses, and said, “I love you so much I could just eat you up”?

The metaphor means that all boundaries between lover and beloved will be overcome. I propose that in the Christian tradition, whatever prepares us to be loved by God with this intensity is called asceticism.

Because it is an act of love, Christian asceticism does not originate from any sort of disgust with this world. Lewis noted that because Nature, and especially human nature, is fallen, it must be corrected, “but its essence is good; correction is something quite different from Manichean repudiation or Stoic superiority.”2 Christian asceticism comes from the willingness to surrender our appetites that we might be taken up into mystical communion with the Trinity. We must choose between two alternatives, Augustine declared in The City of God: “Love of self till God is forgotten, or love of God till self is forgotten.”3

“Imagine a man in whom the tumult of the flesh goes silent,” Augustine rhapsodized in The Confessions. “His soul turns quiet and, self-reflecting no longer, it transcends itself. . . . And imagine [God] speaking. Himself, and not through the medium of all things. Speaking Himself. So that we could hear His word, not in the language of the flesh, not through the speech of an angel, not by way of a rattling cloud or a mysterious parable. But Himself. The One Whom we love in everything.”4

David W. Fagerberg is Associate Professor in the Department of Theology of the University of Notre Dame and the author of The Size of Chesterton?s Catholicism (Notre Dame).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on C. S. Lewis from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor