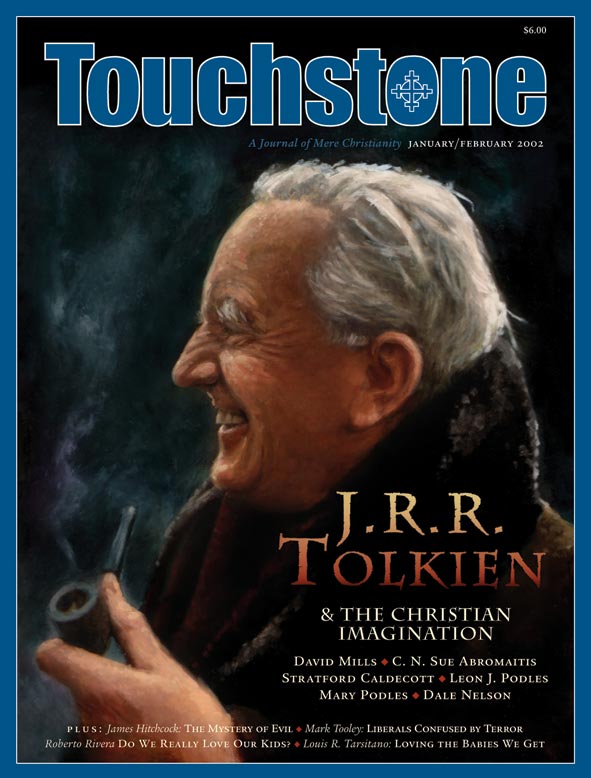

Rings of Love

J. R. R. Tolkien & the Four Loves

by Dale Nelson

A tombstone in Oxford’s Wolvercote Cemetery is inscribed “John Ronald Reuel Tolkien / Beren” and “Edith Mary Tolkien / Lúthien.” Because Beren and Lúthien are the names of husband and wife, lovers, in Tolkien’s writings, and because their equation here with Tolkien himself and his wife is firmly founded on his own conception of the man who married the daughter of an Elf-King and a goddess, as a parallel to his own romance, his inscription hints at an answer, differing from the usual ones, to the question of why The Lord of the Rings has been such a meaningful novel for innumerable readers for nearly half a century: It and the invented mythology from which it was developed are permeated by love.

Readers of a 1960 book by Tolkien’s friend C. S. Lewis will remember that the Greeks discerned four loves: storge, philia, eros, and agape. Tolkien has ensured that it’s not just “given” that the conflict in The Lord of the Rings is between good and evil. He has carefully depicted each of these loves, which provide a constant and persuasive contrast to the Dark Lord’s political and spiritual totalitarianism.

An Origin in Love

To the authors of a newspaper profile on him, Tolkien maintained that Middle-earth originated in his love of language. He said that he liked to invent new languages—but they required people to speak them—indeed, required a world; so he would make that world. But attributing the origin of Middle-earth to the love of languages linked it to his public, scholarly life. The Wolvercote monument, and remarks in Tolkien’s letters, show that Middle-earth drew also upon his most private life—specifically upon his experience of eros, the passionate love of man for woman or woman for man.

Tolkien told one of his sons about his young love for Edith in a letter, written after her death. “I met the Lúthien Tinúviel of my own personal ‘romance’ with her long dark hair, fair face and starry eyes, and beautiful voice” in 1908, when he was 16 and she was 19. Very soon after they married, he was captivated by his wife’s dancing, for him alone, when he was an army officer on leave from the Great War, in 1917, and they slipped away to “a woodland glade filled with hemlocks” in Yorkshire. And that moment was the origin of the myth of Beren and Lúthien, Tolkien wrote to another of their sons.

He refused to give the world an autobiography. His nature expressed itself “about things deepest felt in tales and myths.” He went so far as to identify an enchanted moment in a wood as “the kernel of the mythology” of his imaginary world, in a 1955 letter to his American publishers, but he didn’t tell them about his romance. When we put the evidence of these three letters together, we can see that Tolkien believed that his imaginative world owed its existence not only to his love of languages, but also to his love for one woman, Edith Tolkien.

Furthermore, Tolkien’s world of Middle-earth might never have been realized if not for his affection (storge) for his and Edith’s children. The first-published story of Middle-earth was, of course, The Hobbit (1937). It grew out of stories that Tolkien told at home—young Christopher Tolkien called them “Winter ‘Reads’” that they enjoyed “after tea in the evening.” Eventually Tolkien prepared a typescript, but, according to his biographer, Humphrey Carpenter, Tolkien had not finished it before his sons had “outgrown” it and no longer were asking for winter-evening stories—and “so there was no reason why The Hobbit should ever be finished.”

Tolkien dropped it. If not for the intervention of a family friend who knew someone who worked for the publishing firm of Allen and Unwin, Tolkien might have left the book at the point at which he had arrived, the death of the dragon (with no second climax—no Battle of the Five Armies, in which Bilbo Baggins plays such an important role).

As it was, enough had been written that Tolkien was able to finish the book without requiring very much time. The history of Tolkien’s composition of The Hobbit shows that it was grounded in a father’s love for his children; without them, it would not have been. Without The Hobbit, there would have been no call for a sequel—that is, no call for The Lord of the Rings.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on J. R. R. Tolkien from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor