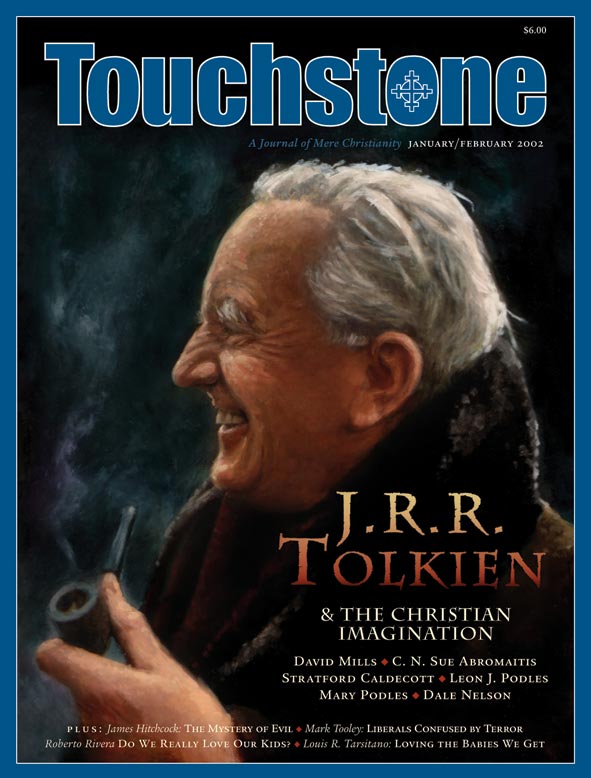

Feature

The Distant Mirror of Middle-Earth

The Sacramental Vision of J. R. R. Tolkien

by C. N. Sue Abromaitis

Most notable about J. R. R. Tolkien’s books is the imagination that created their world. Tolkien himself reflects upon the use of the creative imagination, believing that man, made in God’s image and likeness, shares in the work of God’s creation. At the same time Tolkien is quite aware of his being in a fallen world, one in which he is working against the zeitgeist.

This spirit of the age permeates the artistic depiction of man as the inevitably alienated stranger. The presumption of the age is, in a certain sense, a mixture of two apparently opposed concepts of the real: materialism, reducing all of reality to that which is sense perceptible, and gnosticism, positing a spiritualistic reality available only to the illuminati.

Both mainstream and avant-garde artists and critics adhere to a vision of the world that is materialistic and/or gnostic. Their work essentially denies meaning and harmony, assumes that nothing can be known with certitude, and apotheosizes the self-consciously absurd, nihilistic, hedonistic, anti-heroic, deterministic, and downright ugly.

Ranged against this horror is the sacramental vision that imbues Tolkien’s work, sacramental because Tolkien still sees reflected in the fallen world and its creatures the manifestation of God’s love for man. He believes that all who will open themselves to the epiphanies that surround them can experience this goodness.

Fairy Stories & Fantasy

Tolkien’s literary theory and practice affirm the glorious reality of the world created by God and sees in the beauty of creation proof of the hallowed nature of man. But fallen man needs imagination to perceive this hallowed nature. Tolkien creates his literature to aid that perception. He admits that “one object” of his literary creation is

the elucidation of truth, and the encouragement of good morals in this real world, by the ancient device of exemplifying them in unfamiliar embodiments, that may tend to ‘bring them home’.1

In one of Tolkien’s major theoretical works, the 1947 essay “On Fairy-stories,” he describes the four marks of the fairy story in which “unfamiliar embodiments” can help “bring home” such truth and good morals.

The first mark is fantasy. He uses the word to mean “both the Sub-creative Art in itself and a quality of strangeness and wonder in the Expression, derived from the image.”2 “Fantasy is a natural human activity,” Tolkien concludes.

It certainly does not destroy or even insult Reason; and it does not either blunt the appetite for, nor obscure the perception of, scientific verity. On the contrary. The keener and clearer is the reason, the better fantasy it will make. If men were ever in a state in which they did not want to know or could not perceive truth (facts or evidence), then Fantasy would languish until they were cured. . . . For creative Fantasy is founded upon the hard recognition that things are so in the world as it appears under the sun; on a recognition of fact, but not a slavery to it. (Tree 54–55)

C. N. Sue Abromaitis is Professor of English at Loyola College in Baltimore, Maryland.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on J. R. R. Tolkien from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor