Crazy or Christian?

Preston Jones on a Personal Encounter

The time came for me to say good-bye to Perry. “I’m gonna miss you, man,” he said, rattling my frame in a handshake. “I’ll pray for you first thing every morning, and Little Susie will too.” I could tell by the way he clenched his teeth that he was telling me the truth, and this was one of the very few occasions in my life thus far when I knew that if I tried to say something I would have made a scene. So I instead broke with company policy and hugged him. Then we waved good-bye to one another and I walked away. That was seven years ago, and it was the last time I saw Perry and the locked psychiatric facility that housed him.

My friendship with Perry began well before I actually met him—in the last year of an enlistment in the United States Navy, when I took a sudden and intense intellectual interest in the various forms of psychosis. I read every relevant thing I could get my hands on. So when I showed up at High Mountain Psychiatric Facility1 in Southern California a few days after my enlistment ended, I was able to dazzle its program director with a breadth of knowledge not possessed by the many of her full-time staff. I related all I knew about the most common types of schizophrenia and which psychotropic medications were most often prescribed for which disorders. I recounted the history of lithium and the results of research then taking place at the University of California at Irvine. She claimed to be very impressed but said that she was nevertheless unable to take me on as a mental health counselor since I lacked the appropriate formal credentials. I thanked her for her time, told her she should hire me in spite of her misgivings, and then waited for the job offer I knew would come—which it did, two days later. The morning after her call I ate my first breakfast at High Mountain.

On my first day there I learned that my primary responsibility was to supervise sixteen of High Mountain’s “high functioning” clients. It was in my job description to ensure that they bathed regularly; I was required to encourage them to keep abreast of current affairs; it was my job to help them learn to distinguish the real from the delusional. High Mountain’s goal for most of them was a somewhat normal life in a halfway house somewhere on the outside.

One of my charges was Old Joe, who rarely said anything and who deep down was a nice man. But the fact that he was a killer precluded him from ever being free again. Details of Joe’s crime were unavailable. All that was known was that many years earlier he and a stranger had gotten into an elevator together and everything seemed fine. When the elevator arrived at its destination, however, Joe walked off alive and placid while his riding companion did not. The only other sure thing was that Joe had committed murder with his bare hands.

Then there was Tim, a former Hell’s Angel who took himself for Napoleon or Lewis and Clark, depending on the day. Then there was poor Carlos, who was relentlessly tormented by poisonous, hallucinatory snakes.

When I first met Perry he had just finished having a fistfight with the devil. “Get away from me!” he yelled, swinging wildly in the air. “Someday I’m gonna beat that guy,” Perry said as I walked into his room for the first time.

“Who?” I asked.

“The Old Deluder.”

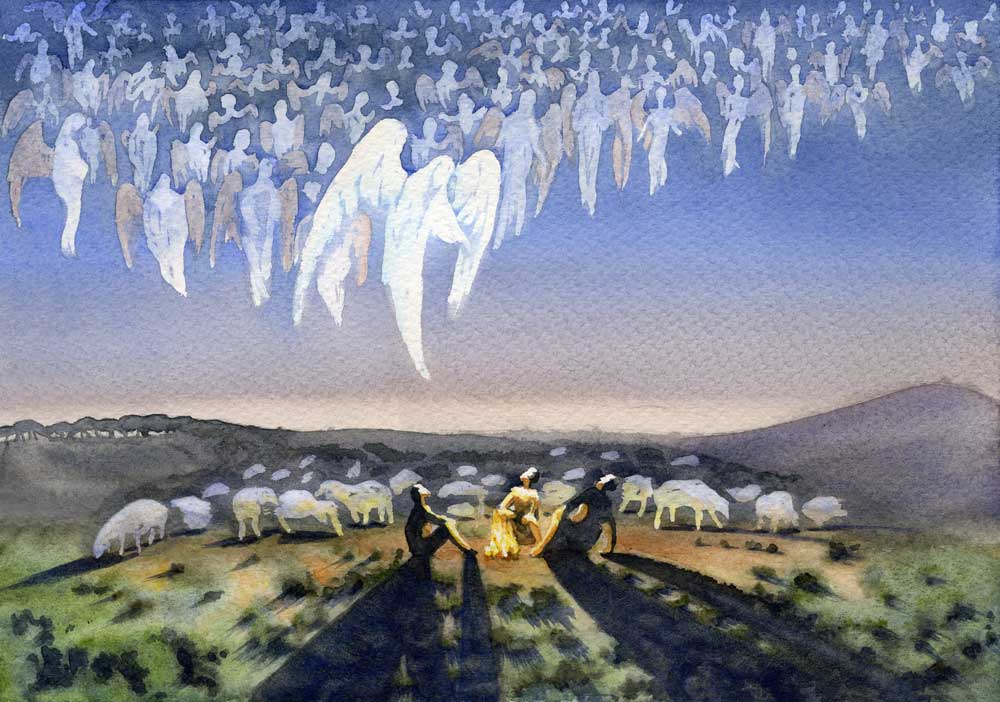

The question was whether Perry was as religious as he was because he was crazy, or whether he was a genuinely devout Christian who just happened to have a mental illness. At one level Perry’s preoccupation with the spiritual world was typical. As is probably the case in most psychiatric facilities, the Bible—particularly the books of Daniel and Revelation—was the text most discussed and read by High Mountain’s residents; and while the voices that accompanied their aural hallucinations were often perceived as coming from the CIA or some other government source, they were just as often construed as messages from angels, demons, both, or from the Lord himself. So Perry’s opinion that the poor quality of a particular lunch was due to the unseen machinations of spirits was nothing special.

Yet Perry was unique. For one thing, he was never given to the sort of grandiosity to which others who claimed to be in close touch with the spiritual world were prone. He never took himself as special. He did everything as best he could and to the glory of God. And he never accepted the occasional praise that was offered him for particular jobs done well. This humility extended even to his playing of pool, his favorite game.

Preston Jones teaches history at John Brown University.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor