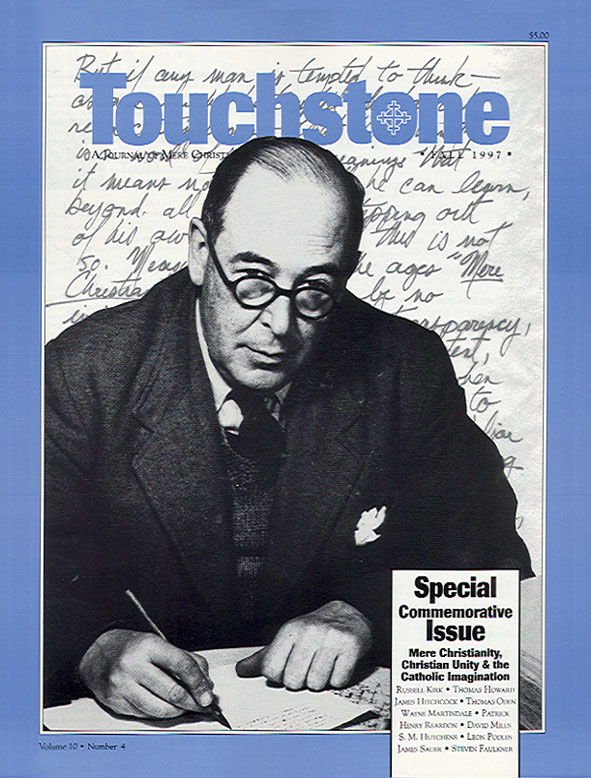

Muggeridge: A Memoir

Malcolm Muggeridge: Journalist, Humorist & Christian

by Thomas Howard

Fifteen or more years ago—I can’t remember just when it was—I came upon Malcolm Muggeridge’s two-volume autobiography, Chronicles of Wasted Time. I knew a little bit about Muggeridge, since I had subscribed to Punch for a year or two while he was its editor. I knew about his droll, dry, wry approach to this oddity that we call human existence, and about his penchant for deflating balloons wherever he came upon them. A wicked and delighted glint seemed to come into his journalistic eyes, as it were (I had not then yet met him) wherever he encountered humbug, swagger, pretentiousness, and puffery in general. I can remember laughing uncontrollably over almost every page in his autobiography.

Making His Acquaintance

The editor of a small underground newspaper in Cambridge, Massachusetts, near where I live, asked me if I would review the Chronicles for his paper. I was glad to do so. Some months later, a letter arrived at my house from none other than Muggeridge himself. Somehow he had seen the review, and, he said in the letter, he had in this case to break a lifelong rule of his not to “answer” reviews. He said that my review had come “whistling across the generation gap,” and that it had brought him great pleasure. I, of course, was ecstatic. I think a letter from the pope or from the Queen would not have been more welcome to me.

As things turned out, I visited the Muggeridges at their cottage in Robertsbridge the next summer. He was waiting for me at the station platform in a ratty old brown cardigan, and we drove back to their place in his Mini-Minor. I can’t remember the conversation from that day, but I came away exhilarated.

Laughter in a Derisory World

Over the next few years we saw each other intermittently, and, in 1978, he stayed for about five days at our house in Beverly Farms, Mass. My memory of that visit is of spending most of the time in peals of laughter. I have never met another human being whose sheer zest for the English language was so rich and hilarious.

One morning, for example, at breakfast, my daughter, then about eleven, announced, “I think I’m growing up to be like Papa.” “This is grievous news,” said Muggeridge without one second’s pause. He took to calling my son, who was eight at the time, The Burrah Sahib, which is some waggish “title” left over from the British Raj that implies, I think, that the gentleman in question is somewhat testy (my son would gnash his metaphorical teeth over such things like stuck doors or knotted shoelaces: he inherits it from me). Once, after some domestic flurry, Muggeridge, in recounting the day’s events to someone who had come in, remarked that my son was feeling a bit “peppery” that day. Another time I mentioned Lady Violet Bonham-Carter to him in some connection. “She had a crop,” he said instantly. (A crop, readers will recall, is that dangling fold of skin under a hen’s chin.) One of his favorite words was “derisory.” As far as I could see, almost everything that we maladroit humans undertake was, in Muggeridge’s estimation, derisory.

The Churchgoer & Convert

By the time he came to stay with us, he was a serious churchgoer. It seemed to matter to him, not only that he go to church with us (we were Anglicans), but that he and I go forward to Communion together. This is especially interesting to me, in that he had said in print that he had never been able to grasp in any very useful sense the mystery that presents itself to us in Communion, of Christ’s Body and Blood. In later years, after both he and I had been received into the Roman Catholic Church, I never got to talk to him about this. I have often wondered whether, by the time he died, he felt that he had got further with the matter.

Muggeridge was taken up enthusiastically by the Evangelicals when he came to the U.S. in the late seventies, since the word had got out that he had “become a Christian.” Certainly he had begun to write and speak much about Jesus.

But I found that he was greatly bemused by just what it was that the Evangelicals fancied he had done. They wanted to hear him say when he had been born again, and so forth. This puzzled him, since, in his view, he had always been looking for the truth, and had concluded decades earlier than this that, if ever anyone in this sad world of ours had spoken the truth, it was Jesus Christ.

He had an almost fathomless nostalgia for God, you might say, all his life; and when, in his latter years, he decided to identify himself publicly as a Christian, and to testify to the truth as he believed it to be found in Christ’s life, death, and resurrection, he felt that this was simply the culmination of his lifelong quest. But he wasn’t altogether clear as to just what it was that the Evangelicals had in their minds as to what he had done.

He told me an amusing thing about a remark Mother Teresa made to him which, I think, may have been one of the catalysts that precipitated him into the Catholic Church. Being a maverick, he was maintaining to Mother Teresa that he thought God needed Christians outside the Church as well as inside. “No he doesn’t,” said the good nun to him tartly. Not long after that, he made his obedience to the ancient church.

The Precincts of Felicity

My wife and I visited him and Kitty in Robertsbridge two or three years ago. They seemed happy: happy in the rural simplicity of their life there, happy in the hordes of people who arrived at their door (at least they greeted everyone with warmth and good cheer that seemed genuine, and must have been), and happy—very happy—in the eager anticipation of death. To them both, it presented itself, not as the Grim Reaper, but rather as the Next Step, so to speak—the step through from this realm of fantasy (one of Muggeridge’s favorite words) into the undimmed precincts of felicity.

We who were the beneficiaries of Muggeridge’s humor and wisdom can only rejoice that he has reached the goal he sought for so long.

Reprinted from Touchstone, Volume 4.2 (1991)

It is precisely when every recourse this world offers has been explored and found wanting; when every possibility of help from earthly sources has been sought and is not forthcoming; when in the shivering cold the last faggot has been thrown in the fire and in the gathering darkness every glimpse of light has finally flickered out. It is then that Christ’s hand reaches out, sure and firm; that His words bring their inexpressible comforts; that His light shines brightest, abolishing the darkness for ever, so that, finding in everything only deception and nothingness, the soul is constrained to have recourse to God Himself and to rest content. —Malcolm Muggeridge |

The published works and collections of the lectures of Malcolm Muggeridge include: Winter in Moscow (1934; 2nd edition, 1987) Jesus Rediscovered (1969) Still I Believe: Lent/Holy Week Talks on BBC (1969) Something Beautiful for God—Mother Teresa of Calcutta (1971) Paul, Envoy Extraordinary (1972) Chronicles of Wasted Time: An Autobiography (2 vol.) (1972) Jesus the Man Who Lives (1975) A Third Testament (1976) Christ and the Media (1977) Things Past (1978) Some Call It Providence (1980) The End of Christendom (1980) Like It Was (1981) In Search of C. S. Lewis (1983) Vintage Muggeridge (1985) Confessions of a 20th-Century Pilgrim (1988) |

THIS ARTICLE ONLY AVAILABLE TO SUBSCRIBERS.

FOR QUICK ACCESS:

Thomas Howard taught for many years at St. John's Seminary College, the Roman Catholic seminary of the archdiocese of Boston. Among his many works are the books Christ the Tiger, Evangelical Is Not Enough, Lead Kindly Light, On Being Catholic, and The Secret of New York Revealed, and a videotape series of 13 lectures on "The Treasures of Catholicism" (all from Ignatius Press).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor