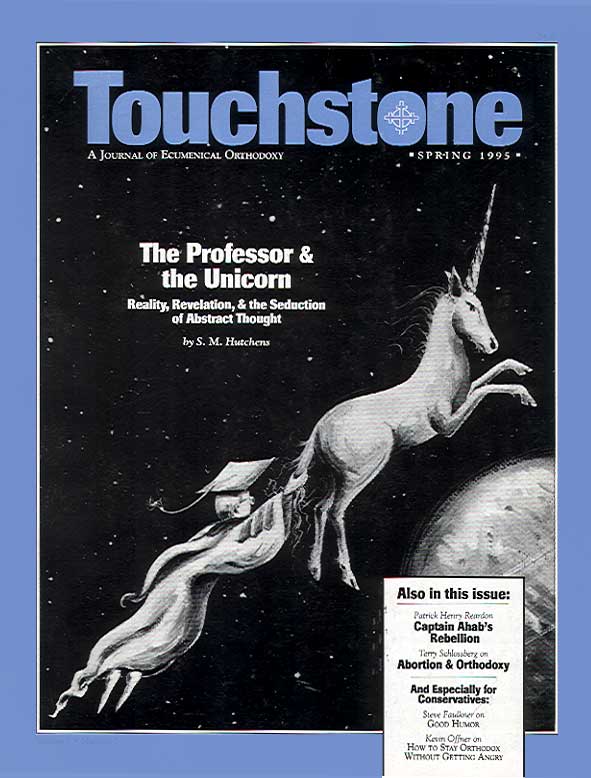

The Professor & the Unicorn

Reality, Revelation & the Seductions of Abstract Thought

by S. M. Hutchens

In a recent series of Touchstone articles and editorials Patrick Henry Reardon and I were called upon to respond to arguments, historical and theological, for the accession of women to church offices traditionally held only by men (see Touchstone, Fall 1992, Winter and Spring 1993 issues). For those who are as weary of this topic as we are, let me say at the outset that this article is not about women’s ordination, but the way of thinking that makes this institution and many others conceivable. One might say it concerns the line between reality and imagination, which, translated into the language of theology, has to do with the difference between revelation and speculation. It is a very old problem that needs to be reconsidered by every generation.

It seemed to Fr. Reardon and me that we were tilting with the unicorn—writing against things conceivable but imaginary. He was dealing mostly with imagined history, and I was speaking against a contrived theology, but we were both speaking to minds abstracted from the reality of the Christian faith as described in its apostolic constitution and lived by the Church. Reardon was confronted with a history of Christian priestesses having so little evidential substance that no reasonable person could consider it anything but a creature of imagination—and yet the imagined idea was strong enough to blind an intellectual giant to Church history as it apparently was, and draw a bishopess (surely kin to the unicorness) out of the catacombs. I faced a theological argument that advanced from Christian premises to non-Christian conclusions on the strength of a concept of equality that defeated history, tradition, and St. Paul’s explicit directives for the role of women in the churches.

We are disposed to shape the world to our desire by elevating notions over verity. This is a corruption of the gift that made homo faber in the image of God. Man who was made to imagine and create within the defined infinity of Truth now makes images of what cannot be. The world is full of his idols, weighted to their own destruction by their inability to answer to reality as it comes from the hand of God. The religious feminist, in the spirit of Antiochus and Pompey, invades the sanctuary and there—aided by the homosexual who also profits from the trivialization of gender distinctions—sets up her egalitarian idea. Those who bow before it finally find themselves in a war against God and nature they cannot win. The same elevation of idea over reality happens when the scientist distorts or ignores the book of nature in favor of his theory, or a nation is molested by political idealists and social architects.

My own experience as a student of theology, in conservative and liberal schools, among Protestants and Catholics, has largely been that of studying ideas about God, his word and will for mankind. The basic material in all cases, even among the most vehement modernists, has been extracted from the biblical mine. But very quickly the idea, separated from the revelational milieu that limits and controls it, takes root and grows on its own. One truth hypertrophies, others atrophy in response, and the school or the sect is born, each with its characteristic preoccupation and error. One segment of Christendom becomes controlled by the idea of bringing the kingdom of God to earth. In others, attributes of God, such as his sovereignty or kindness, or some aspect of the person of Jesus or his Mother, become ground-principles that control the vision of those who adopt them. Distended over revelational boundaries, these ideas are eventually used to attack revelation itself. The phenomenon is the same in all instances—an idea, a generality, not in itself wrong, but given undue license, overcomes the particularity of the Given and conforms everything in its path to its own shape, leaving confusion and schism in its wake.

Conditions on the Western Front

Eastern Orthodox friends tell me that Western theology’s proclivity to err comes from this habit of mind. The difference, they say, between Western theology, shared by Protestants and Catholics, and their own is that here we begin our thinking about God in terms of one of these preoccupations of which I have spoken: an ancient, but non-Judeo-Christian concept of God as Pure or Absolute Being, reflected in the filioque of the Western version of the Nicene Creed and enshrined in our theology by Thomas Aquinas and Protestant Scholasticism. In Eastern Christendom, they tell me, God is contemplated in the revealed mystery of his personhood, of the relation of the Persons of the Holy Trinity to each other and to creation. Once this alleged difference didn’t matter very much to me, since I could not regard the Western theological conversation I had been privy to, considered as a whole, consistent enough to be controlled by any axiology, faulty or otherwise. As as result of my controversy with feminism, however, I have been forced to consider the charge more carefully.

My conclusion is that the Orthodox cannot be blamed too much for generalizing as they do about our understanding of God in the West, but there is something about the inner life of the Catholic and Protestant churches I would like them to appreciate more. It is not true that Christians in the West have devoted themselves to a divine abstraction, that our conception of God is ultimately that of numinous being—and hence a malleable idea—instead of a revealed person. This, rather, has been a driving tendency of our scholastic tradition to which many countercurrents have answered. The history of theology in the West is that of a battleground between the abstract and particular God, the God of Judeo-Christian revelation and the God of speculative reconceptualization. It can be analyzed in terms of ideas of God, set forth in academies that arose as the churches divided—which have always been religious, especially when they claim to be secular—answered by personalistic antitheses that find most of their support beyond their walls.

If we use an analogy derived from C. S. Lewis’s The Abolition of Man, a book with a voice far older than that of its author, we could say we are speaking here of the invidious tendency of the head, abetted by the pride and prejudice of the schools it has created, to rebel against the heart—which has reasons, as Pascal said, of which the head knows nothing. If the heart (Lewis here juxtaposes the Platonic sophia and the Hebrew lev) is where reason and affection are combined by the superior and ultimately mysterious agency of the person himself, we are speaking of a case where the Western head has a history of identifying the heart as mere belly to discredit it and assert control. Visceral faith is present here in force, but not every reaction against the sin of the intellect is a descent into enthusiasm. Sometimes it is the healthy soul’s insistence, which is also found here in the West, that the abstractive, ratiocinative faculty is not qualified to rule the man and must itself be brought under a higher authority in the service of truth.

Those whose studies concentrate on theological literature rather than the actual life of the churches are apt to see the history of Western theology through the eyes of academic theologians, historians of dogma, and the church offices they influence, an ascendancy from which there has been a continuous and powerful revolt. This revolt is against the tendency of an abstractive and formalizing school theology to make clerics by training them in religious philosophy and to make God the property of this clerical caste, with the theological faculty firmly on top. Perhaps the place this is most evident these days is the attempt of Catholic academics to define Catholic faith in defiance of the bishop of Rome, who above all the popes of recent history combines devotion and intellectual power in a heart that has control of both. The pope’s struggle is an old one, fought by many others on a variety of fronts.

The correspondence of Karl Barth and Adolf von Harnack is a fascinating example of this phenomenon. Barth tweaks the nose of the German theological academy on behalf of the Church’s faith. Harnack loftily accuses him of enthusiasm and anti-intellectualism, and in the end doesn’t see how they can carry on an intelligent conversation. The reason Harnack hadn’t the slightest feeling for the Church as a theological authority to which he as a professing Christian is bound is because he was a professor, and therefore not in the slightest measure subject to it. This illustrates the strange end of a long process. What is called theology here in the West has been the province of specialists who have insisted on the privilege of defining the Christian faith with an ever-higher measure of independence from the spiritual life of the churches. What began as special privilege for discussion of doctrine within the universities has grown by our times into almost complete spiritual alienation of imperial theological faculties from the living Church. (My opinion as to why the churches seem nevertheless to welcome, or at least tolerate, the tyranny of the schools, and thus drink their own death, is that the school theologians buy their church salaries and endowments by telling people what they want to hear rather than what the historical faith teaches. Resistance to this morbid cycle rarely comes from the faculties. Often it is spearheaded by a conspicuous traitor from these ranks, like Wycliffe, Barth, or John Paul II, who makes his appeal to the people directly or through pastors who have the courage to swim against the stream.)

S. M. Hutchens is a senior editor and longtime writer for Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor