Uncultured Men & Women

Time magazine recently sensationalized women’s ordination with its front cover claiming that a second reformation is “sweeping” Christendom, as seemingly church after church approves the ordination of women. But the article by Richard Ostling hardly was in keeping with the cover. The article, unlike the cover which presented a fait accompli, respectfully articulated the major differences between the two sides in an ongoing struggle over women’s ordination, as well as over abortion, homosexuality, inclusive language, and trinitarian theology. Ostling correctly discerns a fundamental fault line that finds conservatives and liberals on opposing sides on many of these issues. Writers and speakers defending or debunking women’s ordination usually digress by discussing inclusive language, trinitarian theology, and sexual roles. There are obvious connections between all these issues, and the combatants in these debates, whether by instinct or deliberate plan, bolster their positions or enlarge the territory they deem strategic to their cause by launching into those other issues.

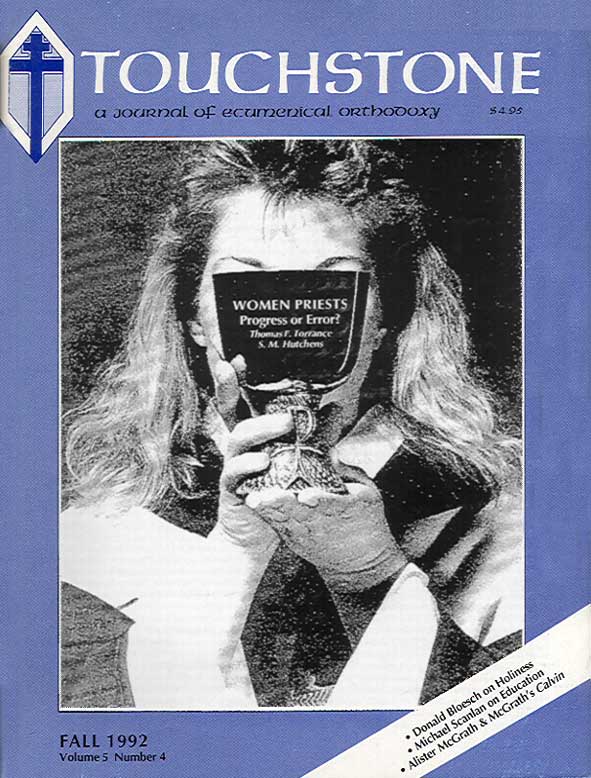

Is the ordination of women based on a new movement of the Holy Spirit who is seeking to overturn nearly two thousand years of what Archbishop of Canterbury George Carey has called a “serious theological error”? Is the Holy Spirit doing this, or is the ordination of women a creeping theological error itself, winning acceptance in significant quarters of the Church, but nevertheless producing schism, disillusionment, and bitterness in its wake? Both sides in this controversy accuse each other of espousing “distorted Christologies” or caving in to cultural demands.

Admittedly, the increase in the number of ordained women and official approval of this—particularly in the mainline denominations, perhaps most notably the Anglican communion—gives the appearance of a movement that is inevitable and reasonable. But critics point out that the movement is not a sign of health: denominations that have approved women’s ordination have been steadily shrinking. The Church of England, which just passed legislation allowing the ordination of women, is now a minority church in Britain: on any given Sunday there are more Roman Catholics at worship than there are Anglicans. Are the churches that ordain women on the cutting edge, bringing the values of the Kingdom of God into society, or are they nearly exhausted, trying to play catch up with society and regain some of the relevance they lost in the ’60s and ’70s? And are those opposed to women’s ordination stalwart defenders of the faith in the face of modern error, or are they old traditionalists on their way to extinction?

To complicate matters, those on both sides do not agree among themselves. Some conservatives hold that ordination is a sacrament; some deny this but understand the basic premises upon which women’s ordination rests to be at odds with the Scripture; others see threats to trinitarian doctrine. Those favoring women’s ordination couldn’t be more diverse: radical feminists favor it in order to overturn patriarchy and create a new church and religion; some Evangelicals see it simply as a biblically faithful interpretation needed in the twentieth-century church and wish to draw the line there, reluctant to admit homosexuals to the pastoral office. This diversity makes it difficult to tell which arguments a given opponent is going to use.

The argument from culture, however, is perhaps the one most often used. It has become so persistent in twentieth-century exegesis of the Scripture that its presence at times is forgotten—like a droning background noise that eventually is taken for granted. What role does cultural context have in biblical interpretation? This question lies at the bottom of much of the debate.

In one view, proponents of women’s ordination hold that the Apostle Paul and other New Testament writers were surrounded by a patriarchal culture that set a low value on women and therefore was naturally disposed toward a male-only priesthood. Others see more simply the general lack of education and training for women in pre-industrialized society as the motive for apostolic writings opposed to women in positions of authority in the Church. This situation, so the argument goes, has changed: women are no longer tied to child-bearing and child-raising and may easily get the same education as men, and since outside the Church they may work as corporate executives and senators, the church can and should open its pastoral offices to women.

A fundamental question is how do we read the Bible in cultural context? How do we know when a command is transcultural—to be applied even when it conflicts with a given culture—and when we are obliged to find a cultural equivalent? Understanding the culture does have a place in understanding Scripture, but there is no standard, no agreement on to what extent cultural context may be used—not to understand Scripture but rather to explain it away. We have for many years used the argument “that was cultural” to explain away, to avoid, to dull the edges of hard sayings in Scripture. We have done this with usury, lawsuits between Christians, marriage, divorce, remarriage, child-bearing, poverty and justice, sexual ethics, and now the roles of men and women. So many of us for so long have taken so many doses of the cultural argument to ease the pain of the hard sayings that we have grown addicted to it. When we are able to flick aside a strongly worded apostolic teaching such as Paul’s (e.g., 1 Cor. 11) which explicitly argues not only from culture but from created order and spiritual reality, then perhaps we should dismiss the Resurrection as culturally conditioned as well. Why not? We could say that given a Semitic preoccupation with the physical, God raised Jesus just so he could get a message to these primitive folks in their own cultural language about eternal life in God. There is no cosmic, theological meaning to the event itself, nor was it necessary for salvation. We might also dismiss the “culturally-conditioned” use of bread and wine by our Lord at Holy Communion so that cheese and soda might do instead. If we pull what appears to be a loose thread of culture from the biblical fabric we may find we have unraveled it beyond repair.

Ironies abound here. For one thing, we might say that God used the culture as an effective tool to communicate by miracle and parable a clear spiritual meaning in the Scriptures. But when it suits us, we say that in portions of Scripture (which we select) culture actually is obscuring a spiritual truth that may be the opposite of what the text says. Further, we point to Paul’s prohibitions against women in authority as proof of his (misogynist?) patriarchal attitudes, and then we use his obvious and close association and ministry with women in other places as clues that women really did function in the forbidden capacity. Better to portray the now defenseless Paul as a schizophrenic than to admit we want to have it both ways.

If we can use cultural arguments to peel away Scripture in order to see the real meaning, then we can use cultural context to evaluate our recent pronouncements that the refusal to ordain women is “error” or “sin.” If an observer two hundred years in the future uses our methods and reviews the cultural setting of the late twentieth-century church, what would he find? A dominant secular feminist movement predating the ordination of women! He would also find a secular acceptance of abortion, homosexuality, the dissolubility of marriage, the optional nature of the traditional family, and that churches were also becoming confused about these things as well. What might our observer think about our pronouncements about the leading of the Holy Spirit? The surrounding culture, after all, would provide an obvious explanation for our innovations.

Beyond cultural context, however, there is something else our future observer would find, much to our shame. He would see a divided church, with no agreement on authority in the Church or how to interpret Scripture. Some of the more traditional churches allow historical criticism to impugn the reliability of the texts, but feel secure as long as there is sufficient scriptural warrant to establish the structures of authority to define and declare what the faith is. Others without such authority structures may fall back on an inerrant original text, praying that the Spirit will help them to interpret it. But there is no agreement on how to interpret it together.

Further, while there is no agreement on the sacramental character of the pastoral office, our observer would also see that the function of the pastorate has changed, due in part to a change in the nature of local churches. There are few churches that function as viable communities any more; they are more like clubs or franchises—there to meet the spiritual needs of busy consumers or to “bless” the significant milestones of life. Many churches have become commuter “communities” formed by mutual need and availability of programs to meet those needs. Pastors may seek positions for the sake of their own self-fulfillment as much as for the counseling of others.

James M. Kushiner is the Director of Publications for The Fellowship of St. James and the former Executive Editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor